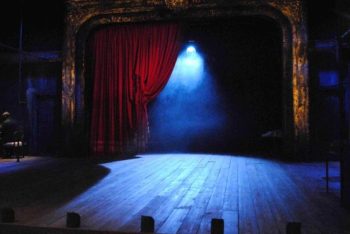

The Stage

Hypocrisy is an art form. If done well, like Cosette in Les Misérables, you will weep with her. However, it is not Cosette you cry with, it is the fine actress that sells you her story. We applaud these hypocrites, for they make us feel, think, even move us to action. Shortly after Charles Dickens wrote the novella, A Christmas Carol, in December of 1843, hearts softened and a spotlight of shame focused on the plight of working-class children. Well done, Mr. Dickens.

I too am a hypocrite, but you’ll not find me on the stage or appealing to your emotions in song. You might call me a navigator, a thought engineer. My hand will be in yours and my arm on your shoulder, but I have no intention to help you, just to help myself to you. You’ll never know my true self, for I’ve honed my craft. Your losses are inconsequential. What matters is that you feel justified. After all, you aren’t to blame for the ills of the world. That’s where I come in, disguised as purpose, justice, or significance. Sit here beside me, for the curtain soon shall open and the grand show begin. Please, watch it with me.

“All is lost,” cries the fisherman, the bay filled with oil shimmering across the gulf like putrid rainbows dotted with bloated fish.

My dreams are made of these things. Opportunity abounds when people suffer. A thirty-million-dollar check for the Climate Policy Initiative, a drop in the bucket compared to the profits from this disaster.

Images of oil-covered gulls gasping for breath, blackened gulf sand, and dying dolphins flash across the screen. The political coffers are opened and fingers point at the greedy barons drilling deep into the earth. Like a grand chess game, castles move and pawns are sacrificed as power and loyalties shift.

Streaming toward the spotlight like desperate moths, once-famous faces cast a troubled hand against their brow, bawling for the cameras like spoiled brats, their crocodile tears flow over botulistic frowns as they vie for center stage. Not all hypocrites are skilled at their craft.

Lights dim as the scene changes. Even I look away from the pleading eyes of a child, her belly distended, dark eyes weary and bombarded by flies.

“Who will help this child?” A soot-covered actress cries, her manicured hands trembling as she collapses and reaches toward the audience.

Plump women in beaded dresses dab their eyes and open their pocketbooks. What’s a thousand when you have a million? The gift assuages guilt, but this child’s belly, and those like her remain empty, the gifts padding bank accounts of marketers and middlemen. I’ve seen this girl, orphaned by war. Little Jathara dies as the camera zooms in to chronicle her plight. For two weeks they follow her over Sudanese sand. The footage, a vulture waiting for her death, earned the journalist a Pulitzer Prize. She died, thirsty and starving.

Did you look away from little Jathara, wondering why the cameraman did not help her?

The curtain closes, a well-timed respite from the edgy scene. On right stage, a young women with almond eyes and long, dark hair, rests a cello on her artificial leg. Saved from the pre-born guillotine in China, the beauty calms the bothered, their contributions collected while she skillfully plays O Sole Mio. As she draws the bow over the final note, the crowd jumps to their feet, the applause and accolades deafening. For a moment, even I love the girl, rescued by Lou Xiaoying, an elderly woman who makes a living recycling rubbish. But the second the curtain opens again, Lynn Zin is both gone and forgotten.

A champion of clean energy takes the stage, tall and handsome in his silk tuxedo. New to the political scene, the young congressman enlightens the gilded. Had I not known better, I’d be taken in myself. Unlike his elder statesman, this novice noble shares his vision with true passion, bolstered by the support of those who plan to use him. Another pawn hawking carbon-footprint credits, not unlike the indulgences Martin Luther so disdained. Whose great cathedral would these credits build, as the ignorant buy their way out of hell?

To the gentleman’s surprise, an award is announced, and two emaciated beauty queens cross the stage and present an engraved plaque with hugs and kisses.

“Do I get to keep them?” He jests, to the crowds delight.

As lights flash, the goddesses giggle and press in close on either side of him, the moment chronicled for tomorrows tabloids and Twitter tweeters. He’s the envy of every man in the theater.

Something creaks and clangs in the rafters. Moving on a cable toward the stage, a giant net commands attention. Show-goers track its course, their heads swiveling like cogs in a machine. On the scrim, a blue whale breaches the surface, then plunges into the waves as the net opens, dropping plastic garbage that overflows the stage, spilling into the orchestra pit. The picture changes and the whale is beached, covered with hungry seabirds. Producing the desired effect, the disgust is palpable. What’s to be done?

Away from the polluted ocean, the scene moves inland to a massive dump in Mexico where shoeless children separate needles from syringes and forage for usable trash. As if they can smell the stench, the audience holds a hand to their nose. It’s all so desperate—so overwhelming.

A matron fans her face as intermission is announced. Shall we get a drink? In the foyer, champagne and teacakes refresh the affected, and politicians work the crowd, shaking hands and feigning attraction for widows draped in diamonds. No one speaks to me, but I’m well known. They’ll seek me out in private, where few can witness the exchange.

Back in our velvet-covered seats, the show continues. The well-written script includes a ray of hope, children smiling as they go to school in Kenya, their uniforms new and their schoolhouse simple. I find this display interesting, since the school is ineligible for public funds. Another show of stolen progress justified by good intentions.

“Education is the key to lifting the impoverished,” a long-time senator claims, his Ivy League years filled with drink ,hallucinations and sex, with a trust fund chaser and purchased diploma, compliments of his father. This particular red-nosed statesman knows me well.

Bored by the spit-shower glimmering in the stage lights, I scan the crowd for new faces. You might think you know whom it is I see. Sure, there’s money here, both old and new, but in the balcony, hidden in the shadows, kingmakers survey the crowd. The world is theirs, handed to them to do as they please, and that’s exactly what they do. They’re not Republican or Democrat, religious or irreligious; they are whatever you expect them to be. Master chameleons that herd the populous from one tragedy to the next for gain; game players moving the pieces. Kings fall when they’re no longer useful. It’s the game I’m familiar with.

Wait … who is that in the last row by the exit? Do you know her? I don’t recall ever seeing her before. As if she can feel my inquisitive stare, she glances up to our private box, catching my eye before turning away. Why is she leaving? The show isn’t over.

In the balcony, the kingmakers stir. They too have noticed her and scramble for the exit. The show holds no interest for me. Stay if you like, but I must know why they follow the plain-dressed women.

Like henchmen, the powerful fan out to find her, scanning the dark streets and alleys.

“Over here!” someone yells, drawing the excited to a vacant building. “She’s up there.”

The six suits cover escape routes and move to the second floor.

“We want to talk to you.” One shouts out from the dust-covered stairway, a hand on his hip.

From the third floor, a brick falls from an aged ledge, her hiding place exposed. Who is this stranger they’ve fixated upon? Overhead, boards creak as she makes a wide arch across the floor, her footfalls light and unsteady. On the sidewalk below, people begin to gather in the lamplight, first three, then more, streaming out of the theater and spilling into the street.

“Who is she?” they call out, their need to know unsatisfied.

On the fifth floor, glass breaks and a shrill scream echoes off the theater. Like hyenas running toward the wounded, the kingmakers follow the trail of blood to the sixth floor. Compelled to follow them, I grasp the railing and follow the dark stairs to the top floor, the moon casting eerie shadows through a broken skylight.

There she is, cowering in the corner, her hand gashed open and clutching her chest.

“We told you to stay away—for your own good.” The voice drips with false sympathy.

“You knew I couldn’t!” she wails, holding her gashed hand up, her only shield.

“Wait!” I call out. “I have nothing to gain from this. I’ve not won her over.”

The kingmakers turn to face me, their empty eyes expressionless. “She’s immune to your appeal.”

Without another word, they cast the woman to the street below, her body twisted and limp. Onlookers move in close to inspect the corpse, their curiosity grotesque. The cameras come, stalling the removal until the paparazzi snap their pictures.

“Who was she?” I ask, watching from a broken window.

“The enemy,” a cold voice replies.

“Nonsense. What’s one woman against the powers of the world?”

The suits turn away and head down the stairs, wiping dust from their pin-striped jackets. People trickle back into the theater, and the show resumes, but many seats remain empty, the stage mundane compared to the woman covered in the street.

I return to my box, my mind reeling as I try to place her. Did you know her?

“The solution,” an aged voice whispers behind us. “Unselfish love.”

“That doesn’t exist,” I scoff, perturbed at the archaic suggestion.

“It is as you say,” the aged agrees, “For she’s breathed her last breath. Without her, we live only for ourselves, manipulated into hatred. It won’t be long now.”

“What’s to come?” I ask, skeptical of this prognosticator.

“The final curtain.”

Image: Pinterest